Real estate boom presents dilemma for assessors across the Adirondacks

When an updated assessment arrived at Anthony Siquier’s residence in Jay, the small business owner was more than a little peeved.

The assessed value on his single-family home on 2.5 acres climbed an acute angle upward to $337,000 from $189,000 in 2021 and $115,000 in 2020, according to property tax records. Tax bill impact: hundreds of dollars more annually in municipal and school district bills.

“It was just totally ridiculous,” Siquier said. The town assessor said it was “based on what houses are selling for in Jay.”

Two houses in proximity to Siquier’s Essex County home, a short drive on State Route 86 in the hamlet of Jay, had recently changed hands at eye popping prices, at least what would have been considered pricey as recently as three years ago.

A recent bubble

Even in New York’s far reaches, home prices appreciated at a rate not seen in more than a decade.

Welcome to the pandemic influenced Adirondack housing bubble. As city dwellers—mostly downstate—found themselves sheltered in their cramped apartments in the work-from-home environment, they often sought refuge far from their former confines, many trekking to the tranquil setting of a home within the Blue Line.

Result: Demand pushed housing prices, particularly in areas with sparse population densities, to record levels. The very real impact can be seen in median home values across the Adirondacks.

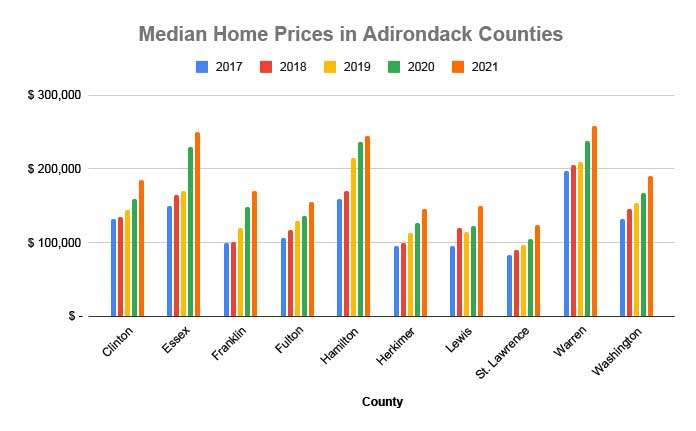

From 2017 to 2021, the median priced home in 11 counties within the Adirondack Park increased at least 30 percent. Franklin County, which extends from Saranac Lake to the Canadian border, leads the pack with a 70 percent increase, according to figures collected by the New York State Association of Realtors. Essex County, Town of Jay’s location, ran a close second with a 67% increase in median home price. Even in Warren County, the laggard, prices increased by 31% from 2017 to 2021. The state real estate group did not register median prices in Saratoga County.

‘Breakneck pace’

Ultimately, there’s a fallout from rising housing prices—reassessment.

“Over the past several months we have seen the real estate market progress to record heights,” the assessor in the Clinton County community of Peru wrote in a message to homeowners. “As a result many property values have increased significantly.”

Assessors throughout the Adirondacks have duly noted the new pricing environment and have reacted accordingly: Reassessing parcels—some of which have maintained age-old assessments. It’s the natural progression from the stark new housing price reality.

Town of Bolton Assessor Christine Hayes has observed and recorded the breakneck pace of real estate sales.

In 2019, the town on Lake George’s western shore reported 58 real estate sales with the highest priced parcel selling for $2.3 million. By 2021, property transfers nearly doubled to 102, with the highest priced parcel selling for $5 million, Hayes said.

There’s no sign of any moderation in real estate values. Through the first half of 2022, Hayes has already seen one property transfer, albeit with sizable lakeside frontage, selling for $8.3 million.

Rising home values present a dilemma for assessors across the Adirondack Park. To keep fair and equitable assessments, those who value homes on an annual basis are required to revalue properties to counter the “Welcome Stranger” syndrome, where newly acquired property is assessed at recent values while other parcels continue at out-of-date assessments because the property has remained in the same hands for decades.

Courts have ruled it is discriminatory to change only the assessment on those properties that were under-assessed and sold, while not altering the assessment on other under-assessed properties that have not sold.

Assessing properties is an odd and sometimes arcane process, those in the field acknowledge. The regular routine is often misunderstood and despised by homeowners because of the potential pocketbook impact.

But indeed, Hayes, the Bolton and Horicon assessor, said the job of placing market value on a parcel and improvements means more than taking in just one year of transactions.

“If you have one sale, that does not make a market,” said Hayes the incoming president of the New York State Assessors Association. “It’s a work in progress. We aren’t just looking at one year. We look at five years.” She said trends within a community are taken into account.

Emotions and frustrations rise when notices of reassessments arrive in the mail. Municipal and school district taxes are pegged to the assessed value of a parcel and the structures, most commonly at a set amount for each $1,000 of value. In the minds of most homeowners, an assessment increase correlates with a rise in property taxes even though fair assessments, in theory, supposedly fairly distribute the tax burden based on a parcel’s market value.

The goal of an assessor, as the Town of Peru assessor explains in his taxpayer letter “is to set a fair and equitable assessment roll where each property owner will pay only their fair share in the tax levy…”

Nevertheless, reassessment can cause wide anxiety within a community as the impact of the annual property tax bill hangs in the balance.

Ideally, all properties within a community are assessed at market value determined “by comparing a property with similar properties that have sold in similar neighborhoods, giving consideration to other factors,” as described by New York’s Department of Taxation and Finance, which oversees and tracks state property assessments.

A community with dated or unfair assessments could subject itself to wide ranging challenges by aggrieved homeowners, creating widespread tumult for assessors.

Assessors in the western Warren County town of Johnsburg recently caused a stir with a collection of reassessment notices.

While neighbors griped, Glenn Pearsall, a financial planner, took it all in stride.

“Although some specific metrics might have been better fine-tuned, I found the process open and transparent—and long overdue,” Pearsall said in an email. “Our assessment went up 20% , which I understand is about the average in the town, and I have no complaints with that.”

Published by Adirondack Explorer